Originally published 30 May 1994

A young Russian student came to my college to study computers. We became friends. When he returned to Russia we exchanged letters.

He never got used to the fact that my letters were typed on a computer and printed on a laser. In Russia, he wrote, it is unthinkable that a personal letter would not be handwritten.

Do Russians retain civilizing graces from times past? Or is it that they have so few personal computers?

I suspect the latter. Yet I concede that there is something inherently gracious about a handwritten letter.

So I took notice when I heard of a company in Oregon called Signature Software that will sell you a keyboard type-font for the Macintosh that looks like your handwriting. You simply fill in a form by hand, reproducing a few dozen nonsense words and an alphabet, and Signature will generate a font that you can install on your computer.

To give the printout the look of authentic longhand, each character is tailored by the software to the characters around it. The result is impressive. I have received a few letters in personal fonts, and if I hadn’t heard about such things, I would have assumed they were handwritten.

OK, so the phony handwriting is a bit of a cheat, but at the same time it adds a touch of humanity to computer communication. If the medium is the message, as Marshall McLuhan said, then the message has just become a tad more personal.

There is progress at the other end, too: Computers are learning how to read longhand.

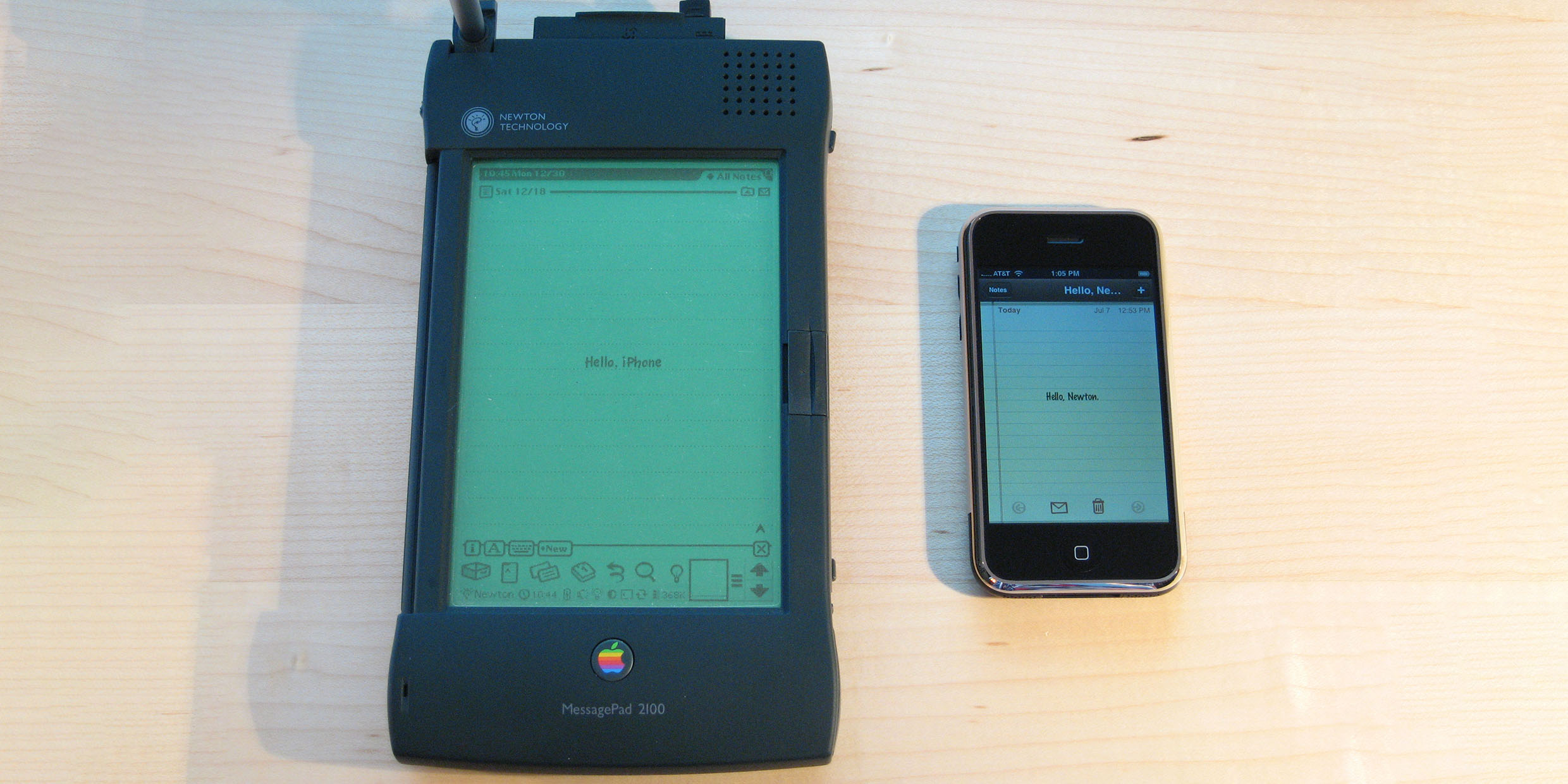

Apple’s hand-sized Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), called Newton, has no keyboard, only a glass screen upon which you write with a plastic stylus. The handwritten words disappear from the screen, replaced by their type equivalent.

Well, sort of. Newton’s handwriting recognition skills are not yet perfect. I wrote, “The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.” The computer interpreted this as “The well-known cox jumped over the lazy key.” I tried again, taking more care with my script. This time Newton came up with “The quiche brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.”

Not bad. Even human interpreters have trouble with my scrawl. And the machine must cope with an almost infinite variety of handwriting styles, both cursive and block. To be fair, I did not give Newton time to learn, for learn it can, if you teach it your personal script.

Computer magazines have panned Newton’s handwriting recognition abilities, and those of a similar stylus-driven device by Tandy/Casio, called Zoomer. But Apple and Tandy/Casio deserve credit for pioneering a technology that will be important in the future.

Machines that respond to voice instructions are also in the pipeline. Several companies are working on voice-driven personal computers. Within five years, many personal computers will respond to both hand-written and voice commands. Keyboards will become an optional accessory.

These new input technologies are a step towards giving machines a human face. The big question is: Can we turn computers into humans before computers turn us into machines?

The challenges faced by designers of longhand and voice-driven machines are formidable. Pattern recognition by computers takes us to the heart of artificial intelligence. Consider, for example, the problem of homophones, words that sound the same but have different meanings (such as “sum” and “some”). A computer must learn to interpret these words in their context, as does the human brain.

Apple’s Newton has something called Intelligent Assistance that allows the computer to anticipate what the user wants it to do, another way of mimicking the human brain. Although the “assist,” as presently executed, is sometimes less than “intelligent,” the achievement is impressive. With Newton, the engineers at Apple are hoping to repeat the triumph of the Macintosh, a user-friendly machine that went a long way toward making computers behave the way we do, rather than the other way around.

It is not hard to imagine personal computers of the future that are as friendly and responsive as pets, ready at a spoken word to do our bidding. In many ways, this may seem a frightening future, but it far less frightening than a world in which humans become automatons at the bidding of machines.

Russia is far away and the mails are slow. It can take a couple of weeks for a letter to reach my friend. However, the day is not far off when we will be connected on the information superhighway. I’ll jot a greeting with a stylus on a glass screen, and the message will be instantly printed in my personal script in Moscow.

In spite of my friend’s misgivings about computer-generated personal missives, we may be heading in the right direction after all. We’ll have the best of both worlds: the convenience and speed of the computer age, and a few civilizing touches from yesteryear.