Originally published 16 November 1992

On June 22, 1633, Galileo Galilei was condemned by a tribunal of the Roman Catholic Church for teaching that the Earth revolves about the sun, rather than the other way round.

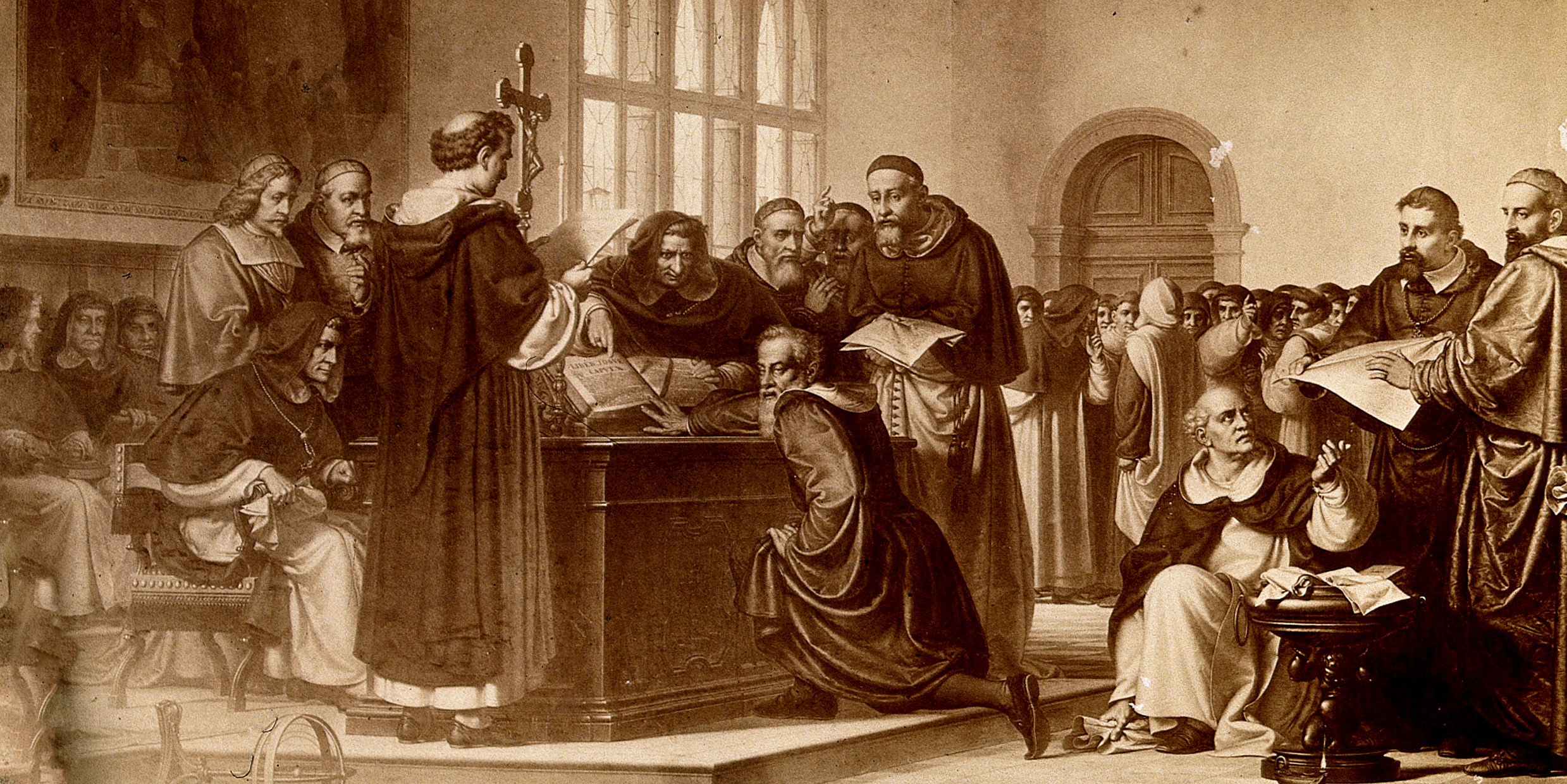

On his knees before the assembled cardinals, the 70-year-old man recanted his belief in the Earth’s motion and renounced his life work. So doing, he escaped torture or death by burning at the stake, and won instead the lighter sentence of house arrest in Florence. It is said that after reciting the official recantation he whispered under his breath, “Eppur si muove”—“Yet it moves.”

Whether Galileo actually whispered the legendary words hardy matters; he surely thought them. He returned to Florence, frail and blind, and continued his experiments in physics.

The Earth went on revolving about the sun.

And a chasm of mutual distrust opened between the Roman Catholic Church and science.

Two weeks ago [in 1992], Pope John Paul II formally proclaimed that the church erred in condemning Galileo. The condemnation resulted from a “tragic mutual incomprehension,” said the pope, and became a symbol of the church’s “supposed rejection of scientific progress.”

Certainly, the condemnation of Galileo involved misunderstandings on both sides, but the phrase “mutual incomprehension” is not quite accurate. Galileo, at least, had a clear comprehension of the issue: In turning its back on the new science the church risked undermining its moral and intellectual authority.

The church’s rejection of scientific progress was more than “supposed”; it was very real, indeed. When I was an undergraduate studying quantum physics and relativity at a Catholic university, I was required to take philosophy and theology courses grounded in Aristotelian physics — more than 300 years after the condemnation of Galileo. Evolution was taught in biology classes, but I was unable to borrow philosopher Henri Bergson’s Creative Evolution from the university library because it was on the list of proscribed books.

That was 35 years ago and much has changed. Philosophy and theology departments at many church-related colleges and universities are now vital centers of modern thought, and lists of forbidden books have been abandoned. But the consequences of the Galileo case are still with us.

The Roman Catholic Church’s truce with evolution is uneasy at best, although more enlightened than the outright rejection by fundamentalist faiths. Questions of the origin of life on Earth, and of origins in general, still bedevil orthodox theologians.

In his book A Brief History of Time, physicist Steven Hawking describes a papal audience he attended with other leading cosmologists at the Vatican. According to Hawking, John Paul II told the assembled scientists that it was all right to study the evolution of the universe after the Big Bang, but that scientists should not inquire into the Big Bang itself because the moment of creation was the work of God.

Like his Renaissance predecessors, the pope makes the mistake of grounding his theology in current physics. The Big Bang theory is only a provisional waystop in a continuing inquiry into origins. It is possible to imagine a universe which had no beginning in time, and Steven Hawking has been instrumental in investigating just such a possibility. Placing the so-called moment of creation off-limits for rational inquiry suggests that the lesson of Galileo has not been learned.

Molecular biology and neuroscience are other areas of potential conflict between the church and science. Biologists of the next century will almost certainly create living organisms from inanimate materials. Computers of the next century may become fully conscious, by any practical test of consciousness. Human consciousness and memory may also yield to scientific analysis. All of these developments will present problems for a theology of the soul grounded in Cartesian mind-body dualism.

The lesson of the Galileo affair is this: It is risky to look for God in the gaps of science, reserving as God’s special province those things we do not presently understand. Gaps have a way of getting filled. Better to identify God with our knowledge, not our ignorance. “All that is wonderful in this world,” said Augustine, “is included in that miracle of miracles, the world itself.”

The photograph that accompanied the newspaper story about the church’s admission of error in the condemnation of Galileo showed John Paul II dressed in Renaissance garb sitting on a Renaissance throne in a Renaissance palace, surrounded by other men (no women) also dressed in Renaissance clothes. All that was missing was the 70-year-old man on his knees on the marble floor. The photograph is symbolic: in spite of the pope’s cautious and carefully-worded proclamation to the contrary, orthodox theology and science remain essentially at odds.

The split is unfortunate.

As a consequence of the Galileo affair, the Roman Catholic church cut itself off from participation in one of the great adventures of the human spirit — the flight of the human imagination into a universe of unanticipated majesty and mystery.

And science, by asserting its detachment from religion, left itself open to charges of intellectual arrogance and moral indifference. The fantastic popularity of pseudosciences such as astrology and parapsychology can be understood as a reaction to what is widely perceived as the dehumanizing tendencies of science.

In going their separate ways, the church and science were both impoverished. The church remained committed to a theology grounded in obsolete science, and science placed itself aloof to the human need for spiritual fulfillment.