Originally published 24 June 1996

The Danish physicist Niels Bohr, the father of atomic physics, was skeptical.

He knew that only the lighter isotope of uranium, uranium-235, was fissionable and could therefore be used to make an atomic bomb. Uranium-235 constitutes less than one percent of naturally occurring uranium. To separate the light isotope from the more common form of uranium would be extraordinarily difficult.

Plutonium-239 is also fissionable, and can be made from uranium. But that process would be equally challenging.

Bohr told his American colleagues that a bomb couldn’t be made without turning the entire country into a giant factory.

Undaunted, the Americans embarked upon the greatest engineering project of all time, the Manhattan Project. At Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington, vast industrial complexes were constructed in record time. Only a few of the people who built and operated these factories knew their purpose — to produce a few pounds of uranium and plutonium.

Workers at both plants were puzzled by the vast quantities of materials going in with nothing, apparently, coming out.

Meanwhile, on a desolate mesa in New Mexico called Los Alamos, a few dozen scientists were trying to figure out how to turn those precious pounds of uranium and plutonium into bombs. Gen. Leslie Groves, who directed the Manhattan Project, once commented, “At great expense, we gathered on this mesa the largest collection of crackpots ever seen.”

The “crackpots” consisted of some of the most brilliant scientific minds of that time or any other time. A list of the names reads like a star roll of 20th-century physics: Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, Emilio Segrè, Robert Wilson, Hans Bethe, Edward Teller, Richard Feynman, Victor Weisskopf, Julian Schwinger, Stanislaw Ulam, Philip Morrison, to name but a few.

Finally, Niels Bohr himself arrived at Los Alamos. Edward Teller was about to remind the great physicist of his earlier skepticism. “You see…” Teller began. Before he could continue, Bohr said: “I told you it couldn’t be done without turning the whole country into a factory. You have done just that.”

This colossal enterprise, involving America’s largest industrial corporations, hundreds of scientists, thousands of engineers, tens of thousands of workers, new towns, roads, airports, pipelines, factories, and a huge part of the nation’s fortune had as its purpose the production of a few chunks of material that could be carried in a hand bag.

And no one but a few “crackpots” had any idea about how or why the enterprise might be successful.

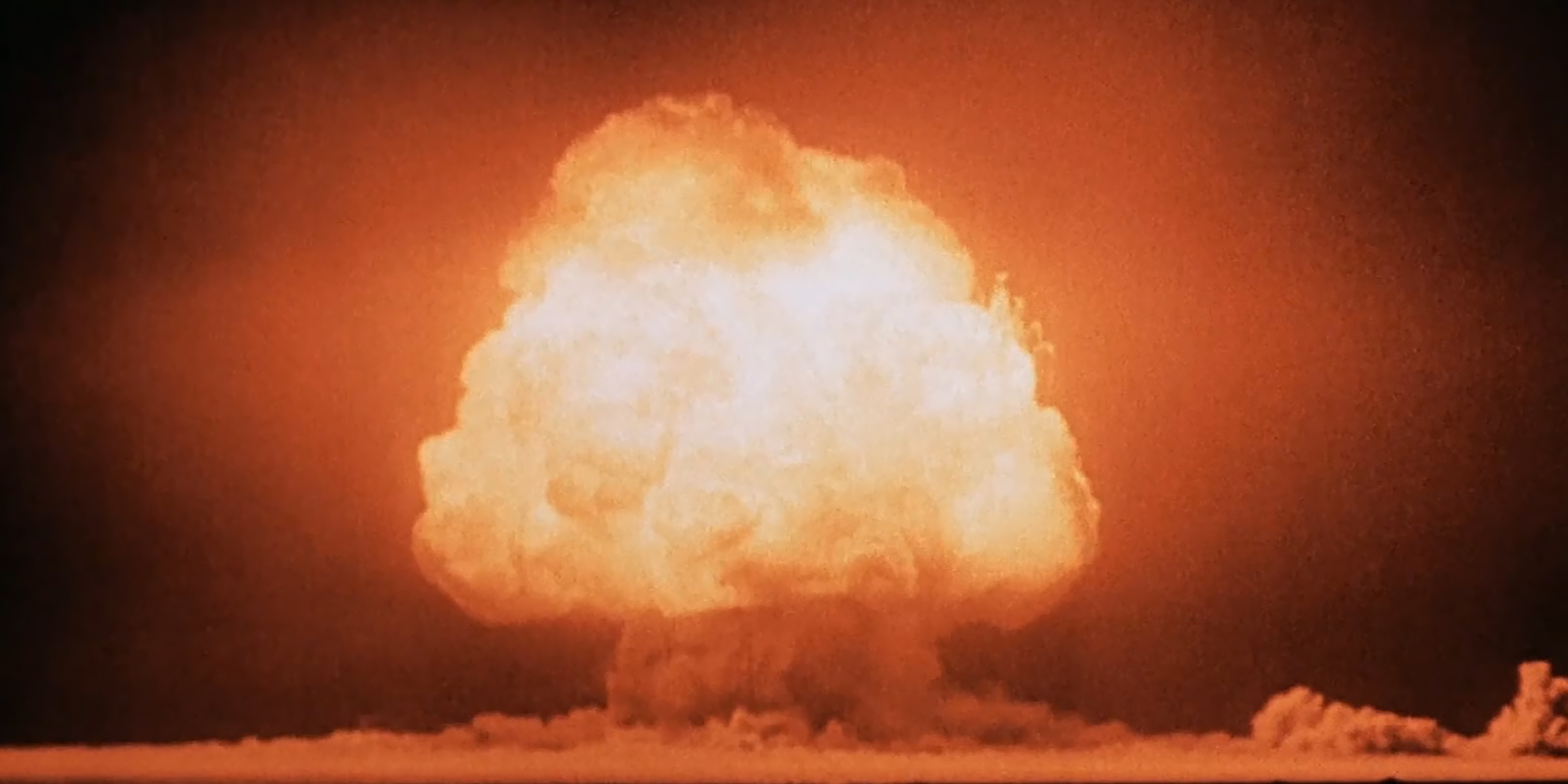

If the test of the first atomic bomb at Alamogordo, New Mexico, in July 1945 had been a dud, the Manhattan Project would have gone down as the biggest scientific, technological, and industrial boondoggle of all time.

Success was equally disturbing. Two cities were obliterated and the world suddenly was made a more dangerous place to live.

When thousands of years from now, the history of the human race is written, the Manhattan Project will occupy a central place — physically, emotionally, morally. When that blazing fireball lit the desert at Alamogordo, humanity crossed a threshold.

No longer were we part of nature; henceforth, for better or worse, we were nature’s master.

The story of the bomb has been told many times, but perhaps never to greater effect than by Rachel Fermi, the granddaughter of the atomic physicist, and Esther Samra in a book called Picturing the Bomb: Photographs from the Secret World of the Manhattan Project.

The book begins and ends with pages from two private photograph albums.

The first is the family album of Jean Critchfield, spouse of Charles Critchfield, one of the bomb makers. It shows their child learning to walk at Los Alamos in February 1944. In its cheery normalcy, it might be the album of any family in America.

The second page is from an album of Robert Serber, a Los Alamos physicist who was among the first Americans to enter Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the Japanese surrender. It shows snapshots of bleak devastation, deserts of rubble and twisted steel.

Fermi and Samra do not moralize, but neither do they shrink from the overarching moral question. The primary epigraph for the book is a quote from Fermi’s grandmother, Laura, who spent the war years at Los Alamos: “I knew scientists had hoped that the bomb would not be possible, but there it was and it had already killed and destroyed so much. Was war or science to be blamed?”

The photographs speak for themselves. Here are startling snaps of ordinary American families engaged in the production of weapons of mass destruction. Here is an unparalleled record of human genius and human violence. Here are the visual documents that show how the devastating power of the stars was released upon Earth by the power of human thought.

Should the bombs have been built? Should they have been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki? The questions nag at our moral conscience like no others. We have heard the questions posed in book after book; now Fermi and Samra give us the family album of the bomb. We read it, the book spread open on our knees, with some awkwardness and embarrassment, as if we were being offered an intimate family album in the home of a stranger.

But these innocent and terrible snaps do not belong to a stranger. They are ours.