Originally published 27 March 1989

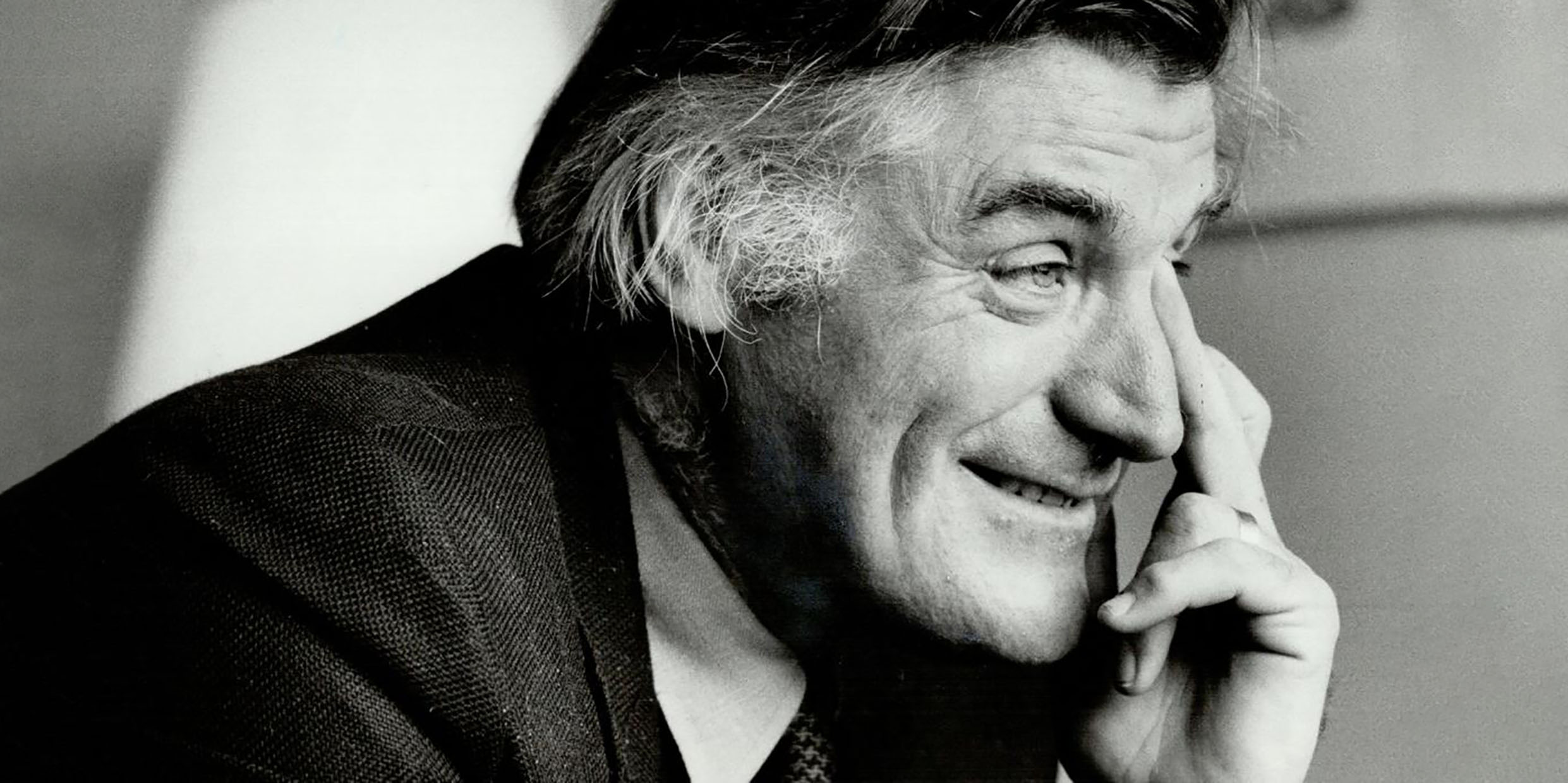

Reaching for a book on a high shelf. Down falls Season Songs by poet Ted Hughes, attracting attention to itself by delivering a lump on the head. I sit on the floor and read again these nature poems written 20 years ago by Britain’s poet laureate.

Fifteenth of May. Cherry blossoms. The swifts

Materialize at the tip of a long scream

Of needle--“Look! They're back! Look!”

At Hughes’ invitation we watch the swifts, those quickest of birds, watch their “too-much power, their arrow-thwack into the eaves.” Arrow-thwack! Yes, that’s exactly right. That’s exactly the way swifts zip into the eaves of the old barn on their evening high-speed revels. As if shot from a bow. Too quick to be animate.

At poem’s end, a lifeless young swift is cupped in the poet’s hand, in “balsa death.” What a phrase! By it we are made to feel the surprising unheaviness of the bird in the hand, the hollowed-out bones and wire-thin struts beneath the skin of feathers, a tiny machine perfected by 100 million years of evolution to skim on air, as light as balsa.

Hughes’ delightful images remind us how much scientists need poets to teach us how to see. Scientists are trained in a very un-metaphorical way of seeing. We are taught to look for immediate connections: X causes Y, Y causes Z. We strip away the superfluous, the non-causal. We isolate. We weigh and measure. The average density of a bird is significantly less than the average density of a mammal of comparable size. That’s one reason birds fly. Balsa wood has nothing to do with it.

But anyone who has held a bird in the hand will recognize the aptness of Hughes’ image — the deceptive lightness, the curious absence of expected heft. The balsa metaphor is instructive. We learn something about birds that no ornithological text quite so vividly conveys.

Make no mistake, I am not dismissing the scientific way of seeing. Weighing, measuring, abstraction, and dissection have proved their worth as royal roads to truth. But the poet’s eye guides us to truths of another kind.

No field biologist has seen “hares hobbling on their square wheels,” but Ted Hughes’ metaphor is so perfectly truthful we can’t help but laugh. No ichthyologist has recorded the mackerel’s “stub scissors head,” but we readily imagine the blunt jaws of the fish shearing open and shut as if operated by a child’s deliberate hand. No astronomer has watched a full moon that “sinks upward/ To lie at the bottom of the sky, like a gold doubloon,” but Hughes’ image truthfully reminds us that there’s no up or down to the bowl of night.

Philosophers tell us that science is metaphorical. They cite, for example, Newton’s “clockwork” solar system and Robert Boyle’s “spring” of air. Christian Huygens, a Dutchman living by water, first thought of light as a “wave.” Alfred Wegener, a meteorologist who traveled in the frozen arctic, conceived of continents drifting like “rafts” of ice. The philosophers are right: At root, scientific knowledge is metaphorical. But young scientists are not trained to think (or to see) metaphorically — and we may be poorer for it.

Metaphor is a way of seeing non-causal connections, as when Ted Hughes speaks of April “struggling in soft excitements/ Like a woman hurrying into her silks.” On the face of it, there’s nothing in the metaphor of use to a scientific student of the seasons, yet the words significantly alter our perception of spring. “Struggle,” “soft,” “excite,” “hurry,” and “silk” force us to think in layers and levels of meaning.

Scientists, especially those working in narrow areas of specialization, are often trapped by tunnel vision. Metaphors have a way of exploding the bounds of perception. Some of the best, most creative science occurs when likenesses are perceived where none were thought to exist. Life is a “tree.” The electron is a “wave.” Thermodynamic systems are “information.”

In his best-selling book Chaos: Making a New Science, James Gleick describes how people working in widely different areas of science came to understand that certain apparently diverse phenomena had much in common. A dripping faucet, a rising column of cigarette smoke, a flag flapping in the wind, traffic on an expressway, the weather, the shape of a shoreline, fluctuations in animal populations and the price of cotton: All these things, it turns out, can be described by a new kind of mathematics — fractal geometry and its variations — based on randomness and feedback. The new chaos scientists, says Gleick, are reversing the reductionist trend toward explaining systems in terms of their constituent parts, and instead are looking at the behavior of whole systems. Their ability to see likenesses between systems is key to their success.

And that’s what poets can teach scientists. Perhaps a course in metaphor should be as important a part of a scientist’s training as a course in mathematics. When Ted Hughes writes…

The chestnut splits its padded cell.

It opens an African eye.

A cabinet-maker, an old master

In the root of things, has done it again.

…he may be on to more than he knows. The old master at the root of things is metaphor.

Excerpts from Season Songs by Ted Hughes, © 1975.