Originally published 28 September 1998

On the evening of March 24, 1882, an unknown country doctor delivered one of the most important scientific lectures of all time to the Physiological Society of Berlin. The audience included some of Germany’s most eminent scientists and physicians, who listened intently as small, bespectacled Robert Koch drew their attention to the table in front of him, where he had prepared glass slides of animal and human tissue for examination under the microscope.

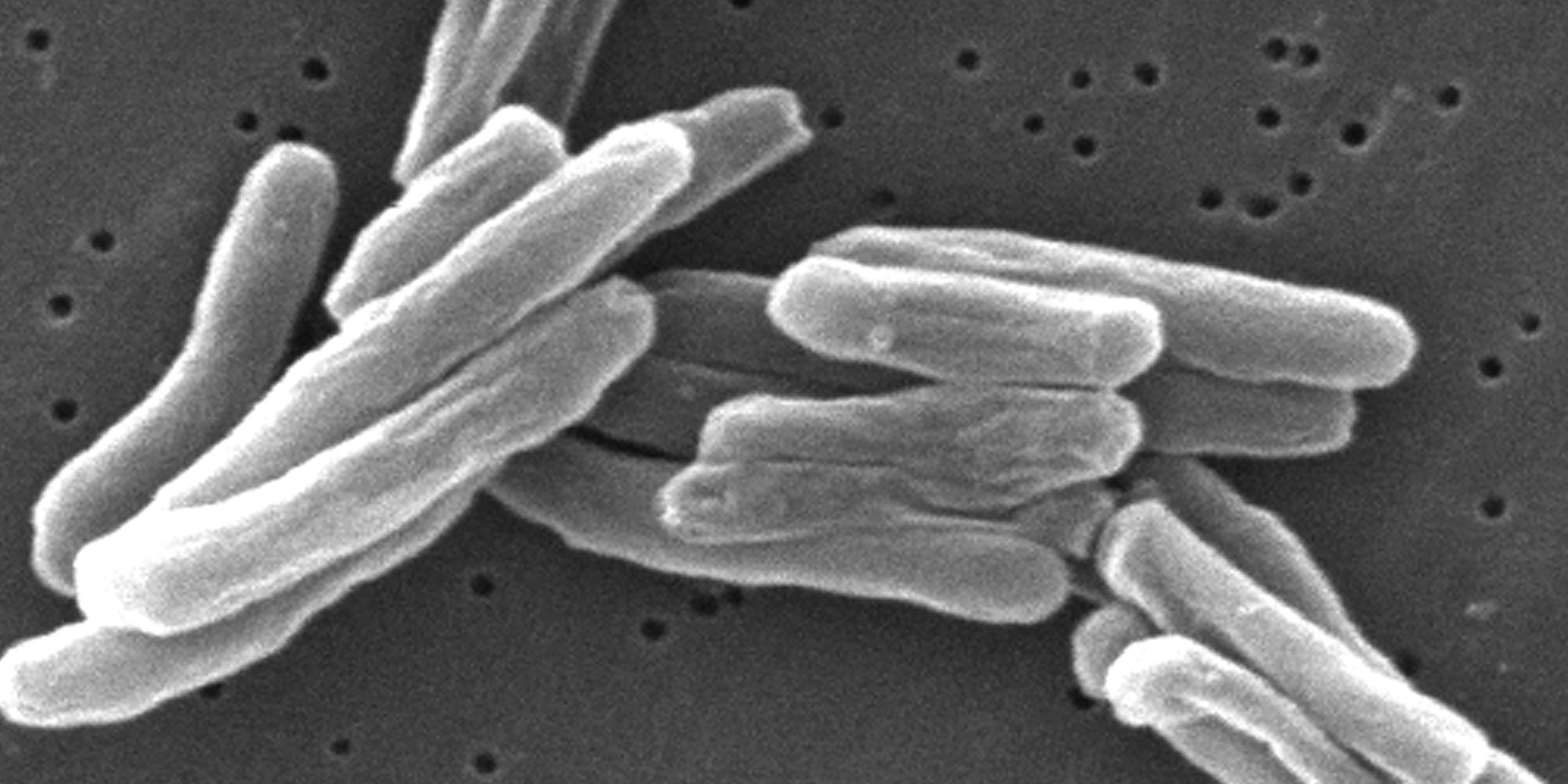

“Now — under the microscope the structures of the animal tissues, such as the nucleus and its breakdown products, are brown, while the tubercle bacteria are a beautiful blue,” he said.

Blue because of a new method of staining developed by Koch that revealed what no one had seen before. There, under the microscope, were microscopically-small, pickle-shaped bacteria, the infectious agent of tuberculosis, mankind’s most persistent enemy, glistening the color of a tropic sea.

Koch’s audience knew they were participating in an historic moment. The 17th-century writer John Bunyan had called tuberculosis “the captain of all the men of death.” The disease wreaked its terrible toll throughout the ages, at least as far back as the Neolithic, among all peoples, on all continents. In the late 19th century, it was feared that tuberculosis might destroy European civilization.

Unlike bubonic plague, which in the Middle Ages swept through Europe in short, swift, killing frenzies, tuberculosis burned with a steady, consuming flame. Its ancient name was consumption — a telling description for the way the disease slowly but surely wasted away infected individuals and entire populations.

Vastly more people harbor the tuberculosis bacteria than develop the disease; perhaps as many as one-third of the world’s population is infected. Generally, the bacillus resides in its human host in a dormant or quiescent state, reproducing at a leisurely pace, causing little harm. Only when the body’s immune system is weakened — by malnutrition, for example — does the pathogen flourish.

Koch’s discovery of the cause of the disease was the first step in a long and ultimately successful search for a cure. By the early 1950s, two drugs, streptomycin and para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS), had proved their ability in combination to knock out the disease.

But the victory wasn’t consolidated. Today, the tuberculosis bacteria—Mycobacterium tuberculosis—continues to take more victims than any other infectious agent. It has evolved new drug-resistant forms. And it has forged a deadly alliance with the HIV virus, which weakens the body’s natural defenses against the tuberculosis bacilli.

A beautiful blue! As Koch observed this devastating killer for the first time, he saw beauty. Beauty and death are not infrequent companions in the quest for knowledge.

Think of Marie Curie’s specimen of radium, collected through years of exhausting work, glowing with an ethereal light in her darkened laboratory; the stuff would eventually kill her.

Think of the ghastly beauty of the mushroom cloud at Alamogordo, rising heavenward, soon to visit obliteration on two Japanese cities.

Think of the beauty of the Challenger spacecraft, climbing on a pillar of fire, exploding like a spectacular fireworks; it carried seven brave astronauts to eternity.

“Beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror,” wrote the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke — and so it has often been with the Janus-faced agents of death, including tuberculosis. In the imagination of romantic poets, composers and writers, tuberculosis conferred a kind a spiritual beauty on its victims: Mimi in La bohème, Alphonsine Plessis in La traviata, Little Blossom in David Copperfield. A character in Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain could say with somber conviction that the disease was “only love transformed.”

And now tuberculosis has shown us another facet of its perverse loveliness. Its genome has been completely sequenced — that is, all 4.4 million chemical base pairs along its DNA double helix have been determined. A map of the bacterium’s protein-building genes was displayed as a five-foot-long fold-out in the June 11th [1998] issue of the journal Nature.

The map is beautifully colored, with a different hue for each functional category of proteins: metabolism, respiration, cell wall, virulence, and so on. The map resembled nothing so much as the score of a great symphony; in this case, the symphony of life.

What we see is not the face of evil — the captain of all the men of death — but the exquisite chemical dynamic that all life shares. The sequenced genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis represents an impressive scientific achievement; it is also beautiful to behold, an atomic music built into the very fabric of the world.

In Nicholas Nickleby, Charles Dickens described tuberculosis as a “disease in which death and life are so strangely blended, that death takes the glow and hue of life.” The same might be said for the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as it is displayed in the fold-out pages of Nature—a lesson in the mortal and amoral dynamic of evolution.

Without death there is no life. Without terror there is no beauty.