Originally published 10 October 1988

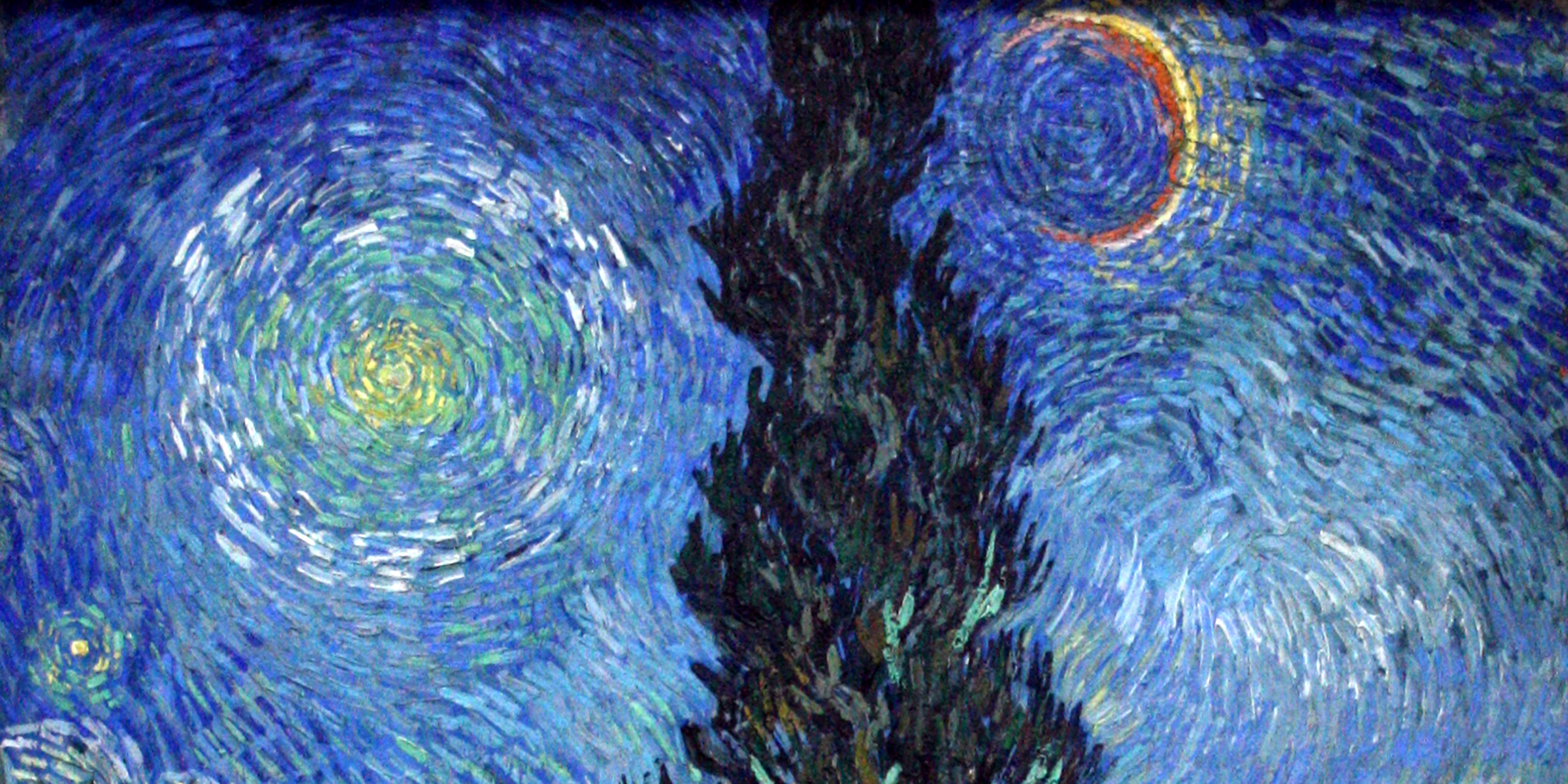

In [a 1988] issue of Sky & Telescope magazine, astronomers Donald Olson and Russell Doescher turn their attention from the real sky to a sky painted by the 19th century Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh. The painting, Road with Cypress and Star, shows three celestial objects — a crescent moon, a bright star, and a less bright star near the horizon. The astronomers asked themselves: Is the sky in the painting the product of the artist’s imagination, or was it inspired by an actual configuration of celestial objects?

Art scholars agree that Road with Cypress and Star was painted at Saint-Rémy, in southern France, near the end of Van Gogh’s yearlong stay at an asylum in that town. The artist left Saint-Rémy on May 16, 1890 for Auvers, near Paris, where he committed suicide two months later.

Using a computer to reconstruct celestial positions, Olson and Doescher worked backwards from the date of Van Gogh’s departure from Saint-Rémy, looking for a likely arrangement of stars and moon.

A crescent moon occurred on April 19. The brilliant evening star Venus was near the moon on that date, and little Mercury near the horizon. The arrangement of the three objects in the sky was strikingly similar to the objects in the painting — except that the order of the objects is reversed left-to-right, and the moon’s crescent is tipped in a way that never happens in the real sky. Despite the differences, the astronomers are convinced that the April 19, 1890 conjunction of Mercury, Venus, and moon was the inspiration for Van Gogh’s painting.

Scientific realism

Harvard astronomer Charles Whitney and UCLA art historian Albert Boime have previously considered other of Van Gogh’s paintings from the astronomical point of view, especially Starry Night over the Rhône and The Starry Night. Whitney and Boime used planetariums to reconstruct past skies, and traveled to France to observe the sky from the places where Van Gogh experienced it. They found several elements of scientific realism in the paintings.

In Starry Night over the Rhône the Big Dipper is easily recognized, although the artist has placed the Dipper, a northern constellation, in a view to the southwest. Boime purports to find Venus and the constellation Aires among the stars of The Starry Night. In the spiraling swirls of The Starry Night both Whitney and Boime see the influence of Lord Rosse’s 1845 drawing of the spiral galaxy M51, known as the Whirlpool galaxy. They guess that Van Gogh may have seen a representation of Lord Rosse’s sketch in the works of the French astronomical popularizer Camille Flammarion.

As Boime makes clear, Van Gogh was keenly interested in astronomy, cartography, and science in general. He was also an exact observer of the night. In a letter to his sister, Van Gogh says that “certain stars are citron-yellow, others have a pink glow, or a green, blue and forget-me-not brilliance.” Stars do indeed exhibit these colors, but only to a careful observer. On this and other evidence, Whitney concludes that Van Gogh had excellent night vision.

Nevertheless, Van Gogh’s skies are unlike any I have seen. His stars are whirling vortices of color, not cold points of distant light. Blue-black night yields in the paintings to torrents of yellow and green. Moons burn with the positive vitality of suns. Space seethes with the energy of flame.

Many people suppose that Van Gogh’s vertiginous paintings of the night are a product of his madness. Art historian Ronald Pickvane rejects this interpretation: “Between his breakdowns at the asylum [Van Gogh] had long periods of absolute lucidity, when he was completely master of himself and his art. That his mind was informed and imaginative, interpretive and highly analytical can be seen in the way he assessed his own work.”

Provocative images

By finding elements of astronomical realism in Van Gogh’s paintings, Olson, Doescher, Whitney, and Boime confirm that these provocative visions of the night are not the products of madness. But neither are they literal representations of the sky. They represent (in Pickvane’s words) “an exalted experience of reality.”

From the barred window of his room at the asylum Van Gogh had an unobstructed view of the night sky. His insomnia gave him ample opportunity to observe the stars. What he put onto canvas was more than what he saw, and more than what a computer or planetarium can reconstruct. In one of his letters he wrote: “I should be desperate if my figures were correct…my great longing is to make these incorrectnesses, these deviations, remodellings, changes of reality that they may become, yes, untruth if you like — but more true than literal truth.”

The painter Georges Braque said: “Art is meant to disturb. Science reassures.” The color-splashed, starry vortices of Van Gogh’s nighttime paintings certainly disturb. They disturb because they evoke something that in our less exalted way we recognize as truer than literal truth. The whirlwind stars of The Starry Night draw us up into a beautiful, terrifying, uncertain universe — a universe in which the individual must sometimes struggle to find security and meaning. Knowing that these wildly turbulent images contain an element of scientific realism is only mildly reassuring.